In this essay, Vijay Padaki examines the dilemmas and prospects of English Language theatre in India.

Vijay Padaki, Academy of Theatre Arts, Bangalore Little Theatre Foundation

Email: vpadaki.theatre@gmail.com Tel. +91 98447 27399

THE ANOMALY OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE THEATRE

In the fall of 2011 I was on an extended lecture-seminar tour of several theatre centres in the USA. It was the 150th birth anniversary year of Rabindranath Tagore, and BLT’s celebrated play based on the Gandhi-Tagore exchanges had two productions in the USA. The responses in every centre were predictably similar –

- Surprise that there was an English language theatre in India

- Surprise that the English speaking segment was just about two percent of the population,

- Surprise, when I revealed it, that neither I nor my writing could truly represent the vastness of Indian theatre

I didn’t have the heart to tell many of them that much of that vastness was facing extinction.

Taking out an Indian currency note I would pass it around and ask the audience what they saw. It is difficult to see (even for an Indian!) that the value of the currency note is printed in fifteen languages. They are all formally recognized National Languages. The prominence of the English language is there for all to see even on the note.

Art and culture in India need English language theatre as health and nutrition need McDonalds. They are quite peripheral to our needs, expensive luxuries and, therefore, dispensable. And yet English language theatre will certainly flourish and grow in India. So will McDonalds. The reasons will be the same.

First, although the clientele for both these products is a very small percentage of the population, located mostly in the cities, in a country of over a billion that small percentage translates to a sizeable market of eyes, ears and mouths.

The second reason is perhaps more significant. Although a small minority in the population, it is a most influential market segment in society. It has been so for a very long time indeed, and is going to remain so. The people in this segment have access to vast resources and the power to influence policy at many levels. How else is it possible to have corporate support for hall rents of nearly a hundred thousand rupees per day, the outlay in twice that amount on print and publicity, the tonnage in stage material and equipment, and so on, all for three to four shows. In contrast, a Kannada production that reaches much larger numbers over very many more shows cannot dream of one fraction of such support? What we are dealing with here is very much the phenomenon of market forces.

Not surprisingly, the single greatest factor in the success of an English language production today is . . . marketing. With marketing comes the savvy of packaging. Packaging the English language theatre production has thus become a major preoccupation for the producer.

No longer can a production be expected to draw good houses on the strength of the name of the play or the playwright or the performing group.

Under these circumstances English language theatre is very often the theatre of indulgence.

We might well respond with: So what? The real danger is in the power of this segment of the market to influence the thinking and lifestyle of the rest of the population, percent by percent, product by product. They so easily set trends that decide for the others what they ought to have, what is good for them, what they ought to believe, what they should be enjoying – in foods, in entertainment, in the theatre. Life imitating art is now no more a mere comic possibility, it has assumed the proportions of a paradigm in global indoctrination.

THE ISOLATION IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE THEATRE

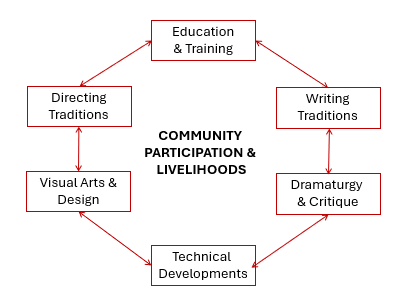

The movement in the theatre cannot be maintained without a true developmental process. (As different from mere growth.) Development is an organic concept. It means that several component features of the larger body must all grow and develop in a necessarily interdependent way. In the theatre, these components may be depicted by the diagram below.

Central to the development process is community participation. If there is a “disconnect” it is often in a vicious cycle, indicating a rather artificially propped up state in the facets, dependent on doles (aka sponsorship) rather than on its own merits. In societies with a vibrant theatre tradition, it is usually in a virtuous cycle, indicating a social investment in the art form.

One of the five facets above, playwriting, is rather like the nutrition supply to keep the body going. As with the choice of foodstuff available to the family, the supply of play material to any theatre company must always be more than abundant. The system must provide ample opportunities to learn the craft and quality oneself, as well as the opportunities to publish one’s work, get them read and critiqued, have them tossed about in workshops, and finally get picked up for formal production.

Good ideas have to stand the test of time. Cleverness in wordplay, contrivances in plot, technical gimmicks, shock value devices – all these have a transient box office appeal to a transient family-and-friends audience. Good dramaturgical sense is something that binds the entire theatre constituency together, including the participating community. We recognize this truth when we experience the delight of being part of a knowledgeable audience.

It must be amply clear that we have a very long way to go in English language theatre to achieve this kind of wholeness in our performances.

THE POTENTIAL IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE THEATRE

We return full circle to the question of the scope of English language theatre in India and its future. The really objective answer to the question will remain elusive. However . . . we are, after all, a reasonably free society and a democratic state. We do protect the interests of the minority. We cannot dream of denying this elite minority its right to choose its goodies and proclaim the flavour of the month. Besides, not all of what is dumped in the marketplace is necessarily harmful for human consumption. For every ton of packaged garbage there is the ounce of silver, the occasional nugget in gold.

Truthfulness to the Indian condition is also possible through original scripts in the English language, thankfully on the increase, although still underdeveloped as a body and struggling for an identity. In the ‘seventies, a small group within Bangalore Little Theatre started on a scripting mission. In the beginning they concentrated on reworking available translations into more stageable scripts. Then came adaptations and, finally, with the confidence gained, attempts at original scripts. Not surprisingly, two of the six awards for contemporary playscripts instituted by The Hindu in 1993 landed in BLT. We cannot get carried away, the craft is still in its infancy.

Precisely because of its fragile condition, the Indian play in English cannot help resorting to its own marketing games. To start with, the script might be written for a western reader or a westernized audience – Indian packaging, but imported content. (Also, western packaging, exotic Indian content!) Like the Indian subsidiary of the multinational, the Indian playwright in English might inadvertently be playing the role of the agent for the western theatre.

We can be sure of the standard response from within the English language theatre circle: Aha, the most eloquent debates on the English language theatre in India are in the English language! While there is undoubtedly some truth in this argument, it is clearly not an adequate answer to the question. It is more a diversion, an avoidance of the complexity of the issue through a simplistic countermove. There are many in the English language theatre who can express themselves well only in that language. Some of them, like this author, are pre-midnight's children, alienated from their mother tongues due to accidents of history. There are several understandable conditions, valid explanations – but they cannot become justifications for our isolation, excuses for continued ignorance of our immediate environment. Most important, these conditions do not give us the license to exploit the market and penetrate it beyond our own perimeters. We must recognize the enormity of the power enjoyed by us in the arts market. We must carry the power humbly, responsibly. Lest we forget, the power we believe we have is not our own. It is derived from the marketplace – now globalized. Somewhere, in some tiny corner of our subconscious, we must know how ludicrous the situation really is. The least we can do is to empower our fellow beings, down to the lowermost twenty percent, to live their own lives, to build their own cultures proudly. And in the end, if we succeed in being accepted as one of them once again, we can seek their forgiveness for trespasses in the past.

-Vijay Padaki

A shorter version of the essay was prepared earlier for Indian Express in 2012 after a US tour.

Vijay Padaki is a Theatre Educator based in Bangalore. As a Founder-Trustee of Bangalore Little Theatre he has been an actor, director, administrator, trainer and writer with the group since its inception in 1960. In 1993 he won The Hindu award for the best contemporary playscript in the English language. Advanced training methodology for actors developed by him is used in the UK and USA. Through the annual Summer Project for newcomers to the theatre (SPOT) he has trained many trainers. Since 2009 he was devoted to the task of setting up an Academy of Theatre Arts under the Bangalore Little Theatre Foundation.

He is the Series Editor of ten volumes of plays being published by Bangalore Little Theatre. He has stepped out of all management responsibilities since the start of 2020, and is currently an Emeritus Trustee.

Bangalore Little Theatre Foundation is a Public Charitable Trust with a non-profit status.

Back

Back